President of the United States of America DONALD J. TRUMP: Large and persistent annual U.S. goods trade deficits have led to the hollowing out of our manufacturing base; inhibited our ability to scale advanced domestic manufacturing capacity; undermined critical supply chains; and rendered our defense-industrial base dependent on foreign adversaries;

FinTech BizNews Service

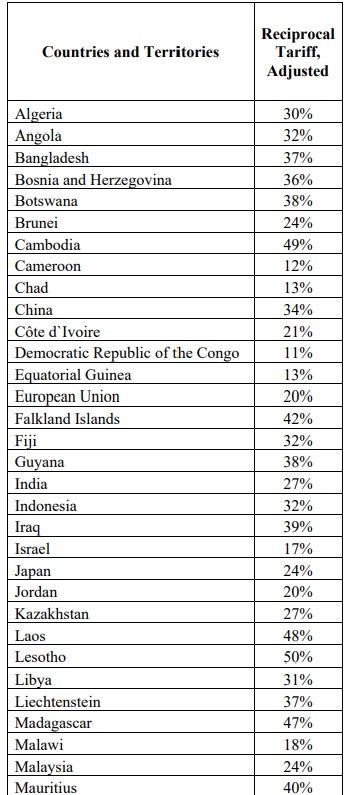

Mumbai, April 3, 2025: DONALD J. TRUMP, President of the United States of America, has announced imposition of 27% Reciprocal Tariff On India on April 2, 2025. TRUMP has announced new country-specific Tariff rates on over 180 countries of the world. TRUMP has announced 10% baseline Tariffs.

National emergency with respect to the threat

As per the details on the website of 'The White House', DONALD J. TRUMP announced on 2nd April: “Underlying conditions, including a lack of reciprocity in our bilateral trade relationships, disparate tariff rates and non-tariff barriers, and U.S. trading partners’ economic policies that suppress domestic wages and consumption, as indicated by large and persistent annual U.S. goods trade deficits, constitute an unusual and extraordinary threat to the national security and economy of the United States. That threat has its source in whole or substantial part outside the United States in the domestic economic policies of key trading partners and structural imbalances in the global trading system. I hereby declare a national emergency with respect to this threat.”

Reciprocal Tariff Policy

It is the policy of the United States to rebalance global trade flows by imposing an additional ad valorem duty on all imports from all trading partners except as otherwise provided herein. The additional ad valorem duty on all imports from all trading partners shall start at 10 percent and shortly thereafter, the additional ad valorem duty shall increase for trading partners enumerated in Annex I to this order at the rates set forth in Annex I to this order. These additional ad valorem duties shall apply until such time as I determine that the underlying conditions described above are satisfied, resolved, or mitigated.

Implementation

(a) Except as otherwise provided in this order, all articles imported into the customs territory of the United States shall be, consistent with law, subject to an additional ad valorem rate of duty of 10 percent. Such rates of duty shall apply with respect to goods entered for consumption, or withdrawn from warehouse for consumption, on or after 12:01 a.m. eastern daylight time on April 5, 2025, except that goods loaded onto a vessel at the port of loading and in transit on the final mode of transit before 12:01 a.m. eastern daylight time on April 5, 2025, and entered for consumption or withdrawn from warehouse for consumption after 12:01 a.m. eastern daylight time on April 5, 2025, shall not be subject to such additional duty.

U.S. goods trade deficits

DONALD J. TRUMP has empathetically announced: Large and persistent annual U.S. goods trade deficits have led to the hollowing out of our manufacturing base; inhibited our ability to scale advanced domestic manufacturing capacity; undermined critical supply chains; and rendered our defense-industrial base dependent on foreign adversaries. Large and persistent annual U.S. goods trade deficits are caused in substantial part by a lack of reciprocity in our bilateral trade relationships. This situation is evidenced by disparate tariff rates and non-tariff barriers that make it harder for U.S. manufacturers to sell their products in foreign markets. It is also evidenced by the economic policies of key U.S. trading partners insofar as they suppress domestic wages and consumption, and thereby demand for U.S. exports, while artificially increasing the competitiveness of their goods in global markets. These conditions have given rise to the national emergency that this order is intended to abate and resolve.

Most-favored-nation (MFN) basis

While World Trade Organization (WTO) Members agreed to bind their tariff rates on a most-favored-nation (MFN) basis, and thereby provide their best tariff rates to all WTO Members, they did not agree to bind their tariff rates at similarly low levels or to apply tariff rates on a reciprocal basis. Consequently, according to the WTO, the United States has among the lowest simple average MFN tariff rates in the world at 3.3 percent, while many of our key trading partners like Brazil (11.2 percent), China (7.5 percent), the European Union (EU) (5 percent), India (17 percent), and Vietnam (9.4 percent) have simple average MFN tariff rates that are significantly higher.

Moreover, these average MFN tariff rates conceal much larger discrepancies across economies in tariff rates applied to particular products. For example, the United States imposes a 2.5 percent tariff on passenger vehicle imports (with internal combustion engines), while the European Union (10 percent), India (70 percent), and China (15 percent) impose much higher duties on the same product. For network switches and routers, the United States imposes a 0 percent tariff, but for similar products, India (10 percent) levies a higher rate. Brazil (18 percent) and Indonesia (30 percent) impose a higher tariff on ethanol than does the United States (2.5 percent). For rice in the husk, the U.S. MFN tariff is 2.7 percent (ad valorem equivalent), while India (80 percent), Malaysia (40 percent), and Turkey (an average of 31 percent) impose higher rates. Apples enter the United States duty-free, but not so in Turkey (60.3 percent) and India (50 percent).

Non-tariff barriers

Similarly, non-tariff barriers also deprive U.S. manufacturers of reciprocal access to markets around the world. The 2025 National Trade Estimate Report on Foreign Trade Barriers (NTE) details a great number of non-tariff barriers to U.S. exports around the world on a trading-partner by trading-partner basis. These barriers include import barriers and licensing restrictions; customs barriers and shortcomings in trade facilitation; technical barriers to trade (e.g., unnecessarily trade restrictive standards, conformity assessment procedures, or technical regulations); sanitary and phytosanitary measures that unnecessarily restrict trade without furthering safety objectives; inadequate patent, copyright, trade secret, and trademark regimes and inadequate enforcement of intellectual property rights; discriminatory licensing requirements or regulatory standards; barriers to cross-border data flows and discriminatory practices affecting trade in digital products; investment barriers; subsidies; anticompetitive practices; discrimination in favor of domestic state-owned enterprises, and failures by governments in protecting labor and environment standards; bribery; and corruption.

Moreover, non-tariff barriers include the domestic economic policies and practices of our trading partners, including currency practices and value-added taxes, and their associated market distortions, that suppress domestic consumption and boost exports to the United States. This lack of reciprocity is apparent in the fact that the share of consumption to Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in the United States is about 68 percent, but it is much lower in others like Ireland (27 percent), Singapore (31 percent), China (39 percent), South Korea (49 percent), and Germany (50 percent).

Structural asymmetries

Trading partners have repeatedly blocked multilateral and plurilateral solutions, including in the context of new rounds of tariff negotiations and efforts to discipline non-tariff barriers. At the same time, with the U.S. economy disproportionately open to imports, U.S. trading partners have had few incentives to provide reciprocal treatment to U.S. exports in the context of bilateral trade negotiations.

These structural asymmetries have driven the large and persistent annual U.S. goods trade deficit. Even for countries with which the United States may enjoy an occasional bilateral trade surplus, the accumulation of tariff and non-tariff barriers on U.S. exports may make that surplus smaller than it would have been without such barriers. Permitting these asymmetries to continue is not sustainable in today’s economic and geopolitical environment because of the effect they have on U.S. domestic production. A nation’s ability to produce domestically is the bedrock of its national and economic security.

Decline of U.S. manufacturing capacity

According to 2023 United Nations data, U.S. manufacturing output as a share of global manufacturing output was 17.4 percent, down from a peak in 2001 of 28.4 percent.

The decline of U.S. manufacturing capacity threatens the U.S. economy in other ways, including through the loss of manufacturing jobs. From 1997 to 2024, the United States lost around 5 million manufacturing jobs and experienced one of the largest drops in manufacturing employment in history. Furthermore, many manufacturing job losses were concentrated in specific geographical areas.

The future of American competitiveness depends on reversing these trends.

Over time, the persistent decline in U.S. manufacturing output has reduced U.S. manufacturing capacity. The need to maintain robust and resilient domestic manufacturing capacity is particularly acute in certain advanced industrial sectors like automobiles, shipbuilding, pharmaceuticals, technology products, machine tools, and basic and fabricated metals, because once competitors gain sufficient global market share in these sectors, U.S. production could be permanently weakened. It is also critical to scale manufacturing capacity in the defense-industrial sector so that we can manufacture the defense materiel and equipment necessary to protect American interests at home and abroad.

In fact, because the United States has supplied so much military equipment to other countries, U.S. stockpiles of military goods are too low to be compatible with U.S. national defense interests.

Going Forward

Furthermore, U.S. defense companies must develop new, advanced manufacturing technologies across a range of critical sectors including bio-manufacturing, batteries, and microelectronics. If the United States wishes to maintain an effective security umbrella to defend its citizens and homeland, as well as for its allies and partners, it needs to have a large upstream manufacturing and goods-producing ecosystem to manufacture these products without undue reliance on imports for key inputs.

In recent years, the vulnerability of the U.S. economy was exposed both during the COVID-19 pandemic, when Americans had difficulty accessing essential products, as well as when the Houthi rebels later began attacking cargo ships in the Middle East.

The future of American competitiveness depends on reversing these trends. Today, manufacturing represents just 11 percent of U.S. gross domestic product, yet it accounts for 35 percent of American productivity growth and 60 percent of our exports. Importantly, U.S. manufacturing is the main engine of innovation in the United States, responsible for 55 percent of all patents and 70 percent of all research and development (R&D) spending. The fact that R&D expenditures by U.S. multinational enterprises in China grew at an average rate of 13.6 percent a year between 2003 and 2017, while their R&D expenditures in the United States grew by an average of just 5 percent per year during the same time period, is evidence of the strong link between manufacturing and innovation. Furthermore, every manufacturing job spurs 7 to 12 new jobs in other related industries, helping to build and sustain our economy.